If you are afraid of speaking in public, then you certainly aren’t alone. Survey after survey has shown it to be one of the things that people fear the most. In a now infamous poll from the 1970s, forty-one per cent of people said they were afraid of public speaking, whereas only nineteen per cent were afraid of death.

Later surveys came to a similar conclusion – that just under half of us dread standing up and talking in front of people. One poll found that only snakes terrify us more. What is it about public speaking that gets a lot of people so riled up? Psychologist Matthias Wieser and his colleagues believe they may have found the answer. In a 2009 study, published in the journal Psychophysiology, they suggest that the anxiety of being in the spotlight means we become more attuned to angry faces. Participants were split into two groups, one of which was told they would shortly be required to give a two-minute speech on a controversial subject that would be judged by a panel of experts. The second group was told that at some stage they would have to write an article about a non-controversial topic.

All participants were then hooked up to EEG machines to measure their brain activity and shown ninety-six flashing images of strangers – a mixture of happy, angry and neutral faces. Those in the public speaking group reacted more quickly to angry faces than their counterparts in the writing group. The authors concluded that we pick up on angry faces more swiftly when we are anxious, re-enforcing the fear of public speaking.

Being more sensitive to the angry members of an audience is likely to mean we overlook the positive feedback being provided by others. If that makes us more fearful of public speaking, then we are likely to be even more anxious next time around. It’s a vicious circle, but help is at hand. According to Daniela Schiller’s 2010 paper in the journal Nature, we can rewrite our fears, as long as we are exposed to them again soon after. So, swiftly get back on the horse by redoing the offending presentation, this time in front of a friendly audience who will nod and smile along.

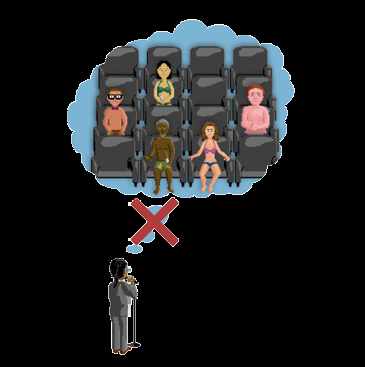

Clearly, many of us find public speaking a challenge – and it seems that might be hard-wired into the way our brains work – and yet it is a key part of career success. So, what else can you do? First, ignore the old cliché that imagining the audience in their underwear will help your confidence as you prepare to speak. There is absolutely no scientific evidence to back up this assertion, and it is likely to be more of a distraction than a help. However, another form of visualization has been shown to be helpful in tasks like these. You just have to do it before your presentation, not during.

It is called “process visualization”. The key is not to picture the outcome of your talk (it going well, people applauding or patting you on the back afterwards) but the steps required for that to happen. That is, you preparing and rehearsing the talk. Then you delivering it to an audience, some of whom will look bored and disinterested, while others lap it up. This approach is backed up by a study published in the journal Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, which showed that students who visualized studying effectively got more A grades than those who visualized getting an A. Likewise, a study published in the Journal of Sport Behavior showed that tennis players who imagined the steps required to get better improved their game more effectively than those who simply imagined they were better at tennis. In short, to be a better public speaker, visualize the steps that you need in order to improve.

If all else fails, then you might consider having lots of sex in the run-up to a big presentation. But it has to be penetrative sex – other forms of intimacy don’t quite cut it. At least that is according to psychologist Stuart Brody. He asked participants to keep sex diaries for a fortnight, logging occasions they indulged in penile-vaginal intercourse, sexual activity with a partner without such intercourse, or masturbation. They were then asked to perform a public speaking task. Brody’s conclusions, published in the journal Biological Psychology, found that the participants who were least stressed out by the task were the ones who had exclusively had penetrative sex over the previous two weeks